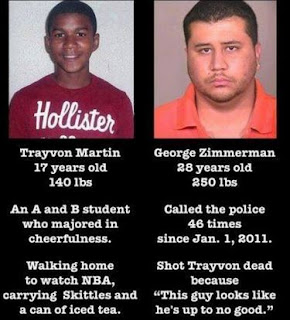

I remember that there was a time in America when shooting an empirically innocent teenager to death would have been considered terrifically wrong under any circumstances. But we Americans are essentially back where we started from at the advent of the post-Rodney King social narrative. The killing of Trayvon Martin in Florida and the subsequent acquittal of his pursuer and slayer George Zimmerman has sparked a flare-up of racial tensions and made a very humbling impression on the prospects for improving race relations in the United States.

In America, perhaps more than any other country, self-absorbed perception is everything. Given this, it has been a national routine for Americans to embrace the comfortable perspective that the image is the reality. It all adds up to the risk of arriving at a lot of appallingly callous conclusions about tense and layered situations. Besieged by the glare of an intrusive media, by a racialized public climate, and by a contentiously legal genre in states with Stand Your Ground laws, the Trayvon Martin verdict made much sense through Florida’s legal process, but absolutely none in the universal web of human morality.

The systematic denouement of the George Zimmerman trial provided succor to those who cling to the idea that you can expunge the racial dimension out of the legal one whenever the behavior of a black man and a white man clash figuratively or literally. Zimmerman’s lawyers were able to take race out of the law and conversely take the law out of race, thereby invalidating race as a judicial archetype in determining the guilt of George Zimmerman. For, if race had been allowed to come into play in the legal proceedings surrounding the Zimmerman trial, the outcome would have been very different.

The prosecution’s eventual failure showed us that there are no obvious signs that racism in America is in some kind of lame-duck phase or what many had hoped was a forthcoming “post-racial” American society with the election of Barack Obama to the presidency. Due to the racial disparities that compromised the prerequisites necessary for a fair verdict in the Zimmerman trial, we must ask in the name of justice what kind of a country do we live in where a common man can be legally shot without having done anything untoward other than being of a certain race? Racism, despite all the progressive advances made in race relations, remains a dirty, uninterrupted vestige of American slavery that can appeal to the worst instincts in the most ignorant of Americans.

There are all sorts of ideas about what went wrong in the Zimmerman trial. When the verdict of not guilty was first announced, a clamor of injustice resonated throughout much of the United States. Many had preconceived notions of legal opportunism, of a virtual trail of blind but potent distinctions of what only a young black man was criminally capable of doing, and of a rigged justice system that had nothing to show in the way of the crusade towards racial equality. Anyway you put it, there was a progressive coalition that tried to turn our attention to the predictable miscarriage of justice with the Zimmerman trial rather than bother with leaving any reasonable room for doubt regarding the final verdict.

Whether or not the Zimmerman verdict was decided in advance by the poisoned fruits of racial interpolations and internalizations even in communities of color such as where Trayvon Martin lived and died in Florida, it is often said by the most mundane of individuals that what is legal in the United States is moral and vice versa. But some of the most utilitarian of laws in America are a step or two behind any moral standards we claim to live by. In rushing towards judgment, we forgot that to a great extent, any nation’s law and morality exist in separate, asymmetrically-shifting worlds.

One last observation: in the course of its unblinking response to the Zimmerman trial, the wider American public stormed into familiar territory where one part of the audience had nothing to complain of, while the other could not be consoled. Indeed, as each side clings to their arguments, less captive audiences are going to be at a loss for a very long time as to how the Zimmerman trial could possibly have preserved a ruling that was right under the law but flawed in every other way.

ALLEN GABORRO

Comments

Post a Comment